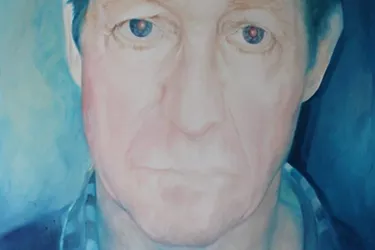

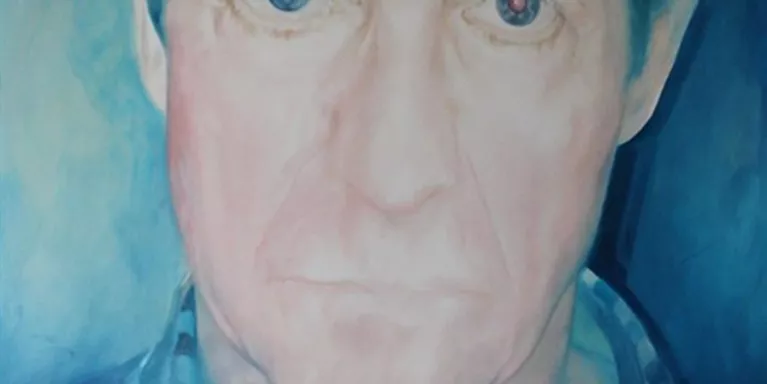

Coming to terms with my mental health at 30

Actor and Guardian columnist Rhik Samadder tells all in this funny, down-to-earth, heartwarming blog about depression and coming to terms with his mental health in his 30s.

Christmas morning, 2010. I’m in bed with my mother, in a Bangkok sex hotel. It is my 30th birthday. How have things got this out of hand?

To wind back a little, I hadn’t been looking forward to a fourth decade. My father had died three years before and I’d responded, with great resourcefulness, by having a comprehensive breakdown, ending a nurturing relationship, and moving back home. I couldn’t work, or go out, and didn’t want to be seen. A life shrunk to four small walls was all that seemed manageable. I was watching the Lion King a lot, and doing all the voices.

"I became extremely sick, something of a signature move."

So when my mother announced we were going to Australia and Thailand for Christmas, I was unresponsive. Having been in the UK since 1979, she had recently become a British citizen and wanted to celebrate, by flying as far away from Britain as geographically possible. She wanted me to see the Great Barrier Reef, she said. I pictured men in shorts, throwing pigskins at my head. But I had no other plans.

The Australian leg was…not good. I became extremely sick, something of a signature move. My mother, basically a toddler, had us pinballing between territories like they were rides at Alton Towers. In three weeks, we flew from Perth to Cairns to Melbourne to Darwin. We spent about 40 minutes in Alice Springs. She was loving it; I was dragging the meat of my own carcass around. We went to Sydney for a single night, which I spent staring at a toilet bowl. In one airport, I looked so rough they nearly didn’t let me on the plane as there was a serious possibility I was carrying bird flu. The night before we left the country, my ex called me on a hotel lobby phone to tell me our dog had died.

"Still, there was everything to play for."

Like I said: not good. Still, there was everything to play for. Christmas in Thailand sounded like an idea from a ‘30 things to do before you’re 30’ peak-experience hit list, the ones that fixate on kayaking, taking ayahuasca on Machu Picchu, or inconveniencing dolphins in Cancun. However, those lists are aimed at sexy young couples who like house music, not a depressed 29 year old and his elderly mother. Don’t imagine beach huts, or tinsel-strewn palm trees. Due to a lack of online hut booking facilities, and mobility issues, we were to spend the week sharing a Bangkok hotel room.

Many people may have a dated, stereotypically seedy mental image accompanying the words ‘Bangkok hotel room’. Those people would be correct. Instead of chocolates, the staff had left condoms on the pillows of the bed. The bed we were sharing. The ‘door’ to the bathroom was a barely frosted glass slat: a saloon door to a nightmare. A week on a porn set was not how I’d pictured becoming a man. At least, not like this.

"Uncommunicative, paralysed, angry with the world."

So there we were, Christmas morning in a Buddhist land, my birthday, no tinsel, surrounded by sex aids. The thing was, with nothing else to do, we sat in the room and talked. I couldn’t remember the last time we had. Depression had left me uncommunicative, paralysed, angry with the world. There is so much shame attached to not being able to function, and I knew my life hadn’t progressed. I was turning 30 having not realized any dreams. I felt small.

Finally talking, though, it became clear none of that stuff mattered to her. I’d done nothing in my whole life to make her proud, yet unfathomably, she was proud anyway. She’d used her savings for us to be able to go away as far away as we could, to show me things, for me to be happy.

"She’d refused to give up on life."

I asked her about her life, which I’d never done, having always assumed I just emerged from a fog in the 1980s. She told me she’d been born in a trench in Burma during the war. How her mother had suffered too much to bear, and died young. How my mother raised her siblings. How later, after the death of my father – her husband – she’d refused to give up on life, and instead taught herself a new skill every year: conga drumming, sculpture, digital storytelling. We talked about what it means to surrender your Indian passport forever, and take a British one. I realized I came from somewhere, which is to say I realized I was alive.

No one tells you the truth about adulthood, which is that you spend most of it missing people, and only a handful of moments last. Sometimes we have to force ourselves to not shut out the people we love, because they’re all that keeps us here. I wasn’t magically transformed that Christmas – I’m still grumpy, ungrateful and complain a lot. But I started to understand; and I started to mend.

"To understand an idea is to own it, and that day I felt the condition weaken its grip."

This was the moment I started to come to terms with depression, and how I got out of it. To understand an idea is to own it, and that day I felt the condition weaken its grip; opening up the possibility that I could slip its chokehold, perform a Russian legsweep and flip myself up to stare down its nostrils. I wanted to bark questions in its face. ‘Where did you come from? Why are you so greedy? Why, if you live inside me, do you want us to die? Why does your breath smell like that?’

I will get no reply, because my adversary is a chemical imbalance in my brain. Or a psychic hangover, oozing through the fractures of childhood. Or a tiny statistic in a social epidemic. Or a genetic hand-me-down, a family heirloom like a box of old spoons. Or a tentacled kraken, unpeopling my vessel, dragging my men down to the depths.

"We need more Tales of Depression."

But I’ll keep talking, because I want to tell my story. Stories bring us comfort, even when they are not comforting stories, because the moral of every one is that whatever we have experienced, we are not alone. They can be a hand in the dark, a reminder that others have struggled, and prevailed. Mental health is perhaps the most serious topic we have, which is why it’s so often boring to read about. But the truth is there is often a great deal of absurdity to our most harrowing experiences, which is a healing thing to remember, when we feel out of joint. We need more Tales of Depression. Gather round children, let’s talk about Great Aunt Stephanie, who sent 60 consecutive tweets to Sandra Bullock because she had no one else to talk to! Have I told you about the time your father cried for three days because he saw a tree that looked like an old man? And wouldn’t let us turn any lights out? He was like a difficult baby! That sort of thing.

In the past I have told myself that I was not human. That I had no family, was marooned from an alien species. Probably a superior species; it’s just the air here wasn’t good for me, which is why I walked double and felt tired all the time. But it’s not true. I just wanted to feel special, to claim compensation for things I had suffered, at the cost of sealing myself away from others. It was incorrect, but it was also a waste of resources. The things that made me feel totally alone then are now what bind me most tightly to others.

Information and support

When you’re living with a mental health problem, or supporting someone who is, having access to the right information - about a condition, treatment options, or practical issues - is vital. Visit our information pages to find out more.

Share your story with others

Blogs and stories can show that people with mental health problems are cared about, understood and listened to. We can use it to challenge the status quo and change attitudes.