A Beginner's Guide to Losing your Mind

Emily Reynolds is a journalist specialising in mental health, technology, science and feminism. Here she blogs about her experience of growing up with bipolar.

One of the things that surprises people when I talk about my experiences with mental illness – other than the revelation that no, weirdly, I can’t just cure it with a positive mental attitude – is how long it took me to be diagnosed.

It was nearly ten years between my first experience of mental illness and my eventual diagnosis with bipolar – ten years of mental health wards, doctor’s surgeries and, most frequently, lying motionless under a duvet.

This isn’t uncommon – the Centre for Mental Health found that children go, on average, ten years before receiving a diagnosis. Of course the reasons for this are complex – anxieties around talking about mental health, GPs unfamiliarity with more severe conditions, cuts to specialist services and more all play a part in diagnoses being missed.

For me, it was a combination of factors. It took me a long time to even visit a doctor, to begin with. What I was feeling didn’t seem normal to me, but maybe it was – discussions around mental health were far less open when I was a teenager, and so I had no real frames of reference.

When I worked out that my inability to concentrate, my constant and viciously low moods and my addiction to self-harm were not, in fact, every day phenomena, I did, finally, get the courage to visit my GP.

"This, it turned out, was a fairly unedifying experience, and my doctor sent me away without much investigation."

Being miserable, he said, was a universal teenage experience. Everyone’s moody when they’re 14, he said! Nobody wants to get out of bed! Self-harm, the most immediately worrying element of my problems, was written off as a fad.

This experience, combined with the fact that my peers at school would also make fun of the fact I self-harmed, was probably one of the most formative - and negative - of my young life. It was only when I was 19, and going through a full-blown psychotic episode, that I sought help again.

And, in more recent years, I’ve experienced similar treatment – one GP told me, in the midst of the worst depressive episode of my life, that I should “see how I feel in two weeks and then come back”, not understanding that in two weeks I might be dead. Halfway through my talking to her about how I was feeling, she stopped me to say that my medical notes stated that I smoked. Would I be interested in quitting?

"Both of these experiences – which should have made me feel hopeful and supported – left me feeling despairing and disempowered."

My first experience led me to doubt myself and, later, to not seek treatment until it was too late. My second unsurprisingly left me feeling even more depressed, even less able to cope and completely phobic of seeking help elsewhere.

Luckily, there are a number of things you can do to prevent this from happening to you. You can’t (or shouldn’t) diagnose yourself, but reading up on and researching mental illness can be a good way for you to work out what it is you might be experiencing.

Logging your own experiences can also be helpful - noting the times and dates of changes in mood or problematic behaviours can give your doctor an insight into what you’re experiencing.

Writing things down like this can also allay anxieties about going to talk to a doctor – you won’t forget what you want to say, and you can present a confident and convincing case for the treatment you need and deserve.

If this doesn’t work, don’t be put off – you can see a new GP in the same surgery or even switch to a different surgery if you’re really uncomfortable. You can also – as I have done, once – complain about your treatment.

And, despite my negative experiences, I’ve also visited doctors who have been helpful, compassionate and empathetic. This, generally, is the norm, so if you’re seeking help for the first time then please don’t be put off.

Getting the right treatment, whether that’s medication, therapy or a combination of the two, isn’t always a fast or simple process, and it may be some time before you settle into treatment.

But seeking help is an important first step in the proactive management of your mental health: don’t feel anything but proud of yourself for doing such a brave, strong and extraordinarily difficult thing.

- Emily's book 'A Beginner's Guide to Losing your Mind' is a candid explanation of mental illness that is both a personal account and a guide to dealing with and understanding it.

Information and support

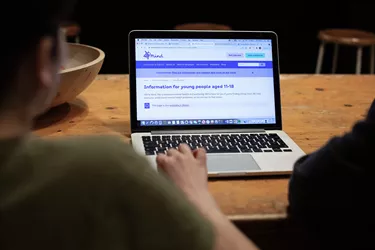

When you’re living with a mental health problem, or supporting someone who is, having access to the right information - about a condition, treatment options, or practical issues - is vital. Visit our information pages to find out more.

Share your story with others

Blogs and stories can show that people with mental health problems are cared about, understood and listened to. We can use it to challenge the status quo and change attitudes.